"Nothing shall deter us from our duty in this eternal struggle -- not death nor prison," Brandon Russell wrote from his jail cell in May 2020. "We are always comforted by the thought of knowing we did the right thing in fighting this wretched System."

The former National Guard soldier was serving a five-year sentence after a former roommate told law enforcement that Russell had explosives and warned them that he had threatened to kill and conduct bombings while cruising neo-Nazi chatrooms.

In a cooler in the garage of the Tampa, Florida, apartment they shared, Russell had HMTD, an explosive used almost exclusively by terrorists that can be made with common materials such as camp stove fuel, hair bleach and over-the-counter supplements.

Read Next: Space Force Done Testing the Fit on its Uniforms, Ending the Loose Pants Saga

Russell, who at the time of his arrest served in the Florida National Guard, had turned the apartment into something of a boot camp for the three men he ushered into the neo-Nazi organization he founded, Atomwaffen Division.

The men used Old Glory as a doormat. A Nazi flag hung on the wall, and Russell had a framed picture on his dresser of Oklahoma City bomber Timothy McVeigh, who had also been a soldier before becoming a terrorist. Their white supremacist group believes violence, terrorism and murder are necessary to eliminate non-white minorities and cause society's collapse.

Russell seemingly went everywhere in his Army uniform, wanting to project an image of "Mr. All-American," one of the roommate's parents would recall. Beneath that uniform, on his right shoulder, the leader had an Atomwaffen Division shield tattoo.

He was released in 2021, but was arrested again in February of this year, along with an alleged female accomplice, and charged with masterminding a plan to blow up Baltimore's electric grid. The goal was to cause as much suffering as possible in the city during times of extreme heat or cold, according to prosecutors.

This story is the second installment in a series on the rise of extremism and the role of troops and veterans. Part 1 looked at how extremist groups are targeting and radicalizing those who have served their country in uniform. Sign up here so you don't miss our next major report.

Atomwaffen, which federal authorities say also now goes by the name the National Socialist Order with an unknown number of members given its disparate cell structure, is just one example of the growing and urgent threat that violent extremists pose to the U.S., according to experts and federal authorities.

And at the lead of some of those organizations, pushed to the front both because of their skills and the respect their service engenders, are service members and veterans like Russell.

"I and several of my closest colleagues for a couple of years now have been kind of looking at each other nervously and saying, 'You know, this feels like the '90s,'" said Amy Cooter, a senior research fellow at the Center on Terrorism, Extremism, and Counterterrorism at Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey.

"This feels like what this movement felt like in the lead-up and the immediate aftermath of Oklahoma City," she said in a recent interview, referring to the deadly bombing by McVeigh in 1995.

McVeigh, who served in the Gulf War, was a "good soldier" who was "real career-oriented," a veteran who served with him told The Associated Press just after the bombing. But after failing to become a Green Beret, McVeigh left the service and turned his hatred against the federal government, traveling to the botched FBI siege of the Branch Davidians compound at Waco, Texas, in 1993 to hand out anti-government flyers.

He murdered 168 people, including 19 children who were mostly in a second-floor daycare center, with a Ryder rental truck packed with explosives that he detonated in front of an Oklahoma City federal building -- the deadliest act of domestic terrorism in U.S. history, according to the FBI.

It was the high-water mark for the last great surge of violent extremism in America. But McVeigh's story looks terrifyingly similar to cases popping up now across the country.

The U.S. intelligence community deemed racially or ethnically motivated violent extremism -- with adherents such as white supremacists, Nazis and other racist groups -- the "most lethal threat" to Americans in its annual 2023 threat assessment released in March.

The groups "believe that recruiting military members will help them organize cells for attacks against minorities or institutions that oppose their ideology," the intelligence report says.

But the Pentagon and Congress remain divided over how seriously to take the threat, even as violent plots are foiled and agencies, watchdog organizations and advocates issue increasingly urgent warnings.

The military services have held stand-downs and issued new policies, but then balked at using up precious time and funding on more elaborate efforts to stamp out white supremacists, Nazis and other hate groups, rather than caring for other pressing issues such as the current recruiting crisis.

"The department did not want to really have to engage this to begin with for a variety of reasons, mainly because it does distract from a lot of the other business and work that they're trying to do," a former official familiar with the Defense Department efforts to combat extremism told Military.com, speaking on the condition of anonymity.

A Message in Blood

New extremist organizations such as Atomwaffen, the Boogaloo movement and the Base, a neo-Nazi group, have picked up where the anti-government militias of the '80s and '90s left off. They seek a violent overthrow of the government or a civil war so they can recreate society, usually into a white supremacist or fascist state.

The accelerationist groups -- the term denotes that they wish to bring about that civil war swiftly -- have sprung up in the aftermath of the Unite the Right extremist group gathering and protests in Charlottesville, Virginia, in 2017. The event was the largest gathering of white supremacists in recent memory, and many of the torch-bearing participants were young men.

But the event, which culminated in a white supremacist driving through a crowd and killing a counter-protester, sent existing groups into disarray.

"The radicals that are left are looking away from those groups and looking toward more active and dangerous paths, such as we've seen in the Hard Reset," said Rick Eaton, a senior researcher and the head of the digital terrorism and hate research team at the Simon Wiesenthal Center, a human rights organization.

The Hard Reset is a manifesto put out by groups such as Atomwaffen on the social media messaging system Telegram through a series of channels nicknamed Terrorgram by both users and experts. The latest iteration of the terrorist how-to magazine published in July included "tactics, techniques, and procedures" on how to bring about societal collapse, as well as 47 pages promoting attacks on infrastructure, according to the Global Network on Extremism and Technology, an initiative at the Department of War Studies at King's College London.

"It's definitely more disturbing than it's ever been, and the willingness to commit violence combined with the general levels of, you know, violent shootings and things in this country are not helping," said Eaton, who has studied extremism at the Wiesenthal center for 37 years.

FBI cases involving domestic terrorism have skyrocketed -- going from 1,981 in 2013 to 5,557 in 2020. Just a year later, in 2021, the number of cases climbed to 9,049, according to a report by the Government Accountability Office.

Racially or ethnically motivated violent extremists were responsible for 94 deaths and 111 injuries over the past decade, the agency reported.

Steven Carrillo, a follower of accelerationist ideology, was an Air Force sergeant at Travis Air Force Base in California in 2020 when he pulled up to a federal courthouse in Oakland, California, in a white van and opened fire on security guards, killing one. He murdered a county sheriff's deputy a week later, all part of a plan to incite a civil war, and was sentenced to 41 years in prison in August.

While on the run before his arrest, Carrillo had scrawled in blood that he believed murdering police, whom he called domestic enemies of the Constitution, would spark conflict between Americans, according to PBS' Frontline.

The list of veterans caught up in extremism in recent years doesn't end there. Two veterans and a soldier are accused of being a Boogaloo movement cell that planned to blow up public infrastructure and terrorize a Black Lives Matter protest in Las Vegas. William Loomis, an Air Force veteran; Stephen Parshall, a Navy veteran; and Andrew Lynam, who was in the Army Reserve, were arrested in 2020 and are still awaiting trial.

Lynam, who was a soldier at the time, told an undercover agent that "their group was not for joking around and that it was for people who wanted to violently overthrow the United States government," according to court documents.

Groups such as the Oath Keepers militia and Patriot Front have preyed on veterans for recruitment, hoping to take advantage of their tactical experience and prestige. Those groups use the language of patriotism and service to appeal to the same character traits that got many to serve the country in the military.

But while experts warn of the gathering threat, extremism has become politically charged after former soldier Stewart Rhodes, the founder of the Oath Keepers militia, and other veterans were convicted of seditious conspiracy for breaking into the U.S. Capitol and disrupting Congress on Jan. 6, 2021, at the urging of former President Donald Trump.

The siege of the Capitol and the disruption of Congress was a stunning development and the most violent attack on the building since British troops set fire to the House and Senate during the War of 1812.

Trump sold the lie that the presidential election was stolen from him and convinced extremists in the Oath Keepers and Proud Boys extremist groups -- as well as hundreds of average Americans -- to attempt to stop the transfer of power to President Joe Biden. Now, Trump is the assumed front-runner in the Republican race for president in 2024.

Just four months after Jan. 6, the Pentagon announced a new working group to combat extremism in the military, after it became clear some troops and veterans were involved in the Capitol insurrection. That included Air Force veteran Ashli Babbitt, 35, who was shot and killed by outnumbered Capitol police as she and other rioters broke down doors to the Speaker's Lobby and House floor, where lawmakers were huddled.

Lloyd Austin, Biden's defense secretary and the first Black person to hold the position, also ordered a one-day stand-down for troops across the services to talk about military values and the oath of service and to get a better understanding of extremism in the ranks.

The Republicans on the powerful Senate Armed Services Committee protested the moves, claiming the anti-extremism effort was part of a political narrative and that it was devastating to military morale. Some continue to question whether extremism is really a top threat.

In March, U.S. intelligence officials briefed senators on the 2023 risk assessment. Sen. Tom Cotton, R-Ark., one of many GOP critics of efforts to root out extremism in the military, needled the officials over the report findings on racially or ethnically motivated violent extremist groups.

"Are you serious? You seriously think that racially and ethnically motivated violent extremists are the most lethal threat that Americans face?" Cotton said during a public hearing.

"So, yes, sir, in terms of the number of people killed or wounded as a consequence," Director of National Intelligence Avril Haines said.

'Destroying Kids' Careers'

The Pentagon's extremism working group wrapped up in December 2021. Austin determined that "very few" troops are involved in extremism, but also noted that even a small number of cases can have an outsized effect on unit morale and cohesion -- and can pose a danger to other service members.

The working group report found fewer than 100 cases of "prohibited extremism activity" in service members over the prior year.

The Defense Department inspector general also reported 281 extremism investigations during just the first nine months of 2021, in what has been some of the only additional data released publicly on the issue in the military. Of those cases, 92 involved some sort of punishment by the military and 83 were referred to civilian law enforcement.

But Jon Lewis, a research fellow at the Program on Extremism at George Washington University, said in a recent interview that the numbers alone fail to recognize a core tenet of terrorism: The quantity of extremists is immaterial to their potential impact.

"It's a prominent, significant issue because it doesn't take 35 guys piling into a U-Haul," Lewis said. "It doesn't take a mass mobilization movement of 30,000 people to the U.S. Capitol. You just need a couple people. You just need one or two with easy access to firearms and a target."

At the Pentagon, military guidance was overhauled at Austin's order to include a voluminous new definition of prohibited extremist activity across the services.

Troops were explicitly barred from advocating or using violence to overthrow the government or push a racist, sexist or discriminatory ideology. Recruiting for extremist causes, extremist paraphernalia such as flags and bumper stickers, and posting or sharing extremist information online are all banned.

But it remains to be seen how the new guidance will be used. The challenge for the military is how to identify the activity in a total force of about 2.3 million, and how to deal with troops who do break the rules, many of them being young adults barely out of high school.

"They're typically junior enlisted that saw some memes or a Reddit thing or watched something on YouTube, heard a guy say something. And the question is whether or not they have full-on engaged in any actual activity," the former government official told Military.com.

If a service member has not fully participated in extremism, then "you're not trying to go out and just destroy these kids' careers," the official said. Instead, intervention to correct and educate them may be a better choice for the military.

"The other piece of the issue is ... within the potential extremist activity movement or issue, the majority of bad actors tend to be veterans -- the vast majority," they said.

But sometimes the most dangerous extremist threats do begin with posts online, and that activity, when not caught or flagged, can end in violence.

Alligator Alley and a Florida Nuclear Plant

One of Brandon Russell's first online screen names was "Odin," a reference to the powerful Norse god of wolves and ravens.

That's how Alan Arthurs remembers hearing about him. Arthurs' son Devon was one of Russell's roommates. Devon, who is now imprisoned in Florida and charged with a double murder, let the name slip during a car ride together. It was a decade ago -- before the deaths and criminal charges -- when his son was still just a wayward teenager.

"I said, 'Excuse me, what?' I thought, wait a minute, who would have the audacity to use that as their screen name?" Arthurs told Military.com in a recent interview. "And that's when all of a sudden I looked at Brandon, or any communication he was having with Brandon, in a different way."

But Devon looked up to Russell like he was amazing. As if he really was a god.

"One of the big trends that I think you see there, and then you continue to see in the neo-fascist acceleration space -- so Attomwaffen and the Base as examples -- is individuals like Brandon Russell ... intentionally targeting younger individuals or even sometimes minors, for recruitment," Lewis said.

Even in Russell's early posts on the now-defunct Iron March website, a notorious online gathering place for neo-Nazis, the former Guardsman tried to present himself as some type of master strategist and influential figure, Lewis said.

"When you really boil it down, it is power and control," he said.

When reached for comment, Russell's attorney Ian Goldstein said, "Due to the pending charges, we have no comment at this time."

In May 2017, Devon Arthurs was arrested for allegedly killing two of his three roommates, sparing only Russell.

"All I know is I got a phone call -- I was at the office -- from Devon telling me that he had shot them," said Arthurs, recalling a conversation with his son immediately after the incident.

It was after his arrest that Devon would describe details of bombing plots the men allegedly hatched, and Russell would head to prison on explosives charges.

Devon told authorities that, before he killed his two roommates in the Tampa apartment, they had planned to attack power lines along the long stretch of Interstate 75 in South Florida known as Alligator Alley.

Those original Atomwaffen members also planned to attack a Florida nuclear power plant, Devon Arthurs said.

Russell would continue on with the effort after his arrest and imprisonment, authorities claim.

He had chosen a new screen name after serving his 60 months on the explosives charges. This time, while out on supervised release, he was going by the name "Homunculus" on encrypted communications.

In June, Russell allegedly started encouraging a FBI informant via encrypted chat to attack electrical substations in a way that would cause maximum damage. The plot would allegedly grow to five electrical substations, according to prosecutors, leading to his February arrest.

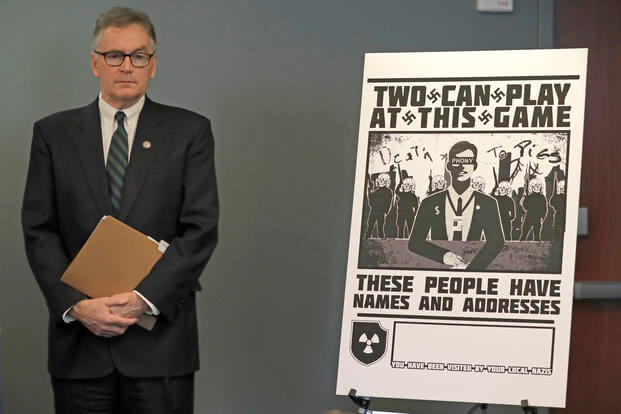

Russell and others in the violent accelerationist movement have also found ways to reach out beyond their neo-Nazi and fascist peers and threaten those in the public who oppose them.

Kris Goldsmith, an Iraq combat veteran, runs Task Force Butler, a nonprofit that researches extremism. His work caught the attention of Russell, he said in a recent interview, and the neo-Nazi targeted his family.

"One of the last things he did before he was picked up by the FBI for planning terrorist attacks, was he shared my home address and photos of my family with his network at Atomwaffen," Goldsmith said.

After Russell posted Goldsmith's information, someone called the police pretending to be Goldsmith, claiming he had a weapon and was going to kill himself. A SWAT team was called out to Goldsmith's house at night while he and his wife were in bed.

The dangerous practice is called "swatting" and is used by Atomwaffen against perceived enemies, such as churches, Islamic centers, universities, journalists and public officials. A Texas man described as an Atomwaffen division leader by federal authorities was recently sentenced to three and a half years in prison for swatting attacks on 134 locations across the U.S.

"Our dogs were barking like f---ing crazy," Goldsmith remembered. He got up and went downstairs to see what had gotten them so excited, running right into armed members of the SWAT team.

"I look outside, and I see a man in dark clothing wearing tactical gear and carrying an AR-15. He points it at my face," he said.

-- Travis Tritten can be reached at travis.tritten@military.com. Follow him on Twitter @Travis_Tritten.

-- Drew F. Lawrence can be reached at drew.lawrence@military.com. Follow him on Twitter @df_lawrence.

-- Konstantin Toropin can be reached at konstantin.toropin@military.com. Follow him on Twitter @ktoropin.

-- Steve Beynon can be reached at Steve.Beynon@military.com. Follow him on Twitter @StevenBeynon.

Related: Trading on Patriotism: How Extremist Groups Target and Radicalize Veterans